Gross Primary Production estimation

Quantifying gross primary production (GPP) is essential for understanding land-atmosphere carbon exchange (Kohler 2018), ecosystem function, and ecosystem responses to climate change (Guan et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2021; Myneni et al., 1995). GPP is the total amount of carbon fixation by plants through photosynthesis (Badgley et al., 2019). With recent advances in technology for remote sensing and more computational power available with lower costs (Gorelick et al., 2017), global mapping of photosynthesis is being done by more scientists (Ryu et al., 2019). Given that GPP cannot be directly estimated from satellite remote sensing techniques, the use of vegetation indices has been a widely used method to approximate and quantify GPP (Ryu et al., 2019). However, estimates remain with high uncertainties and validation efforts are required to characterize these and improve accuracy. (Anav et al., 2015; Brown et al 2021)

Show code

knitr::include_graphics("img/experimental_3.png")

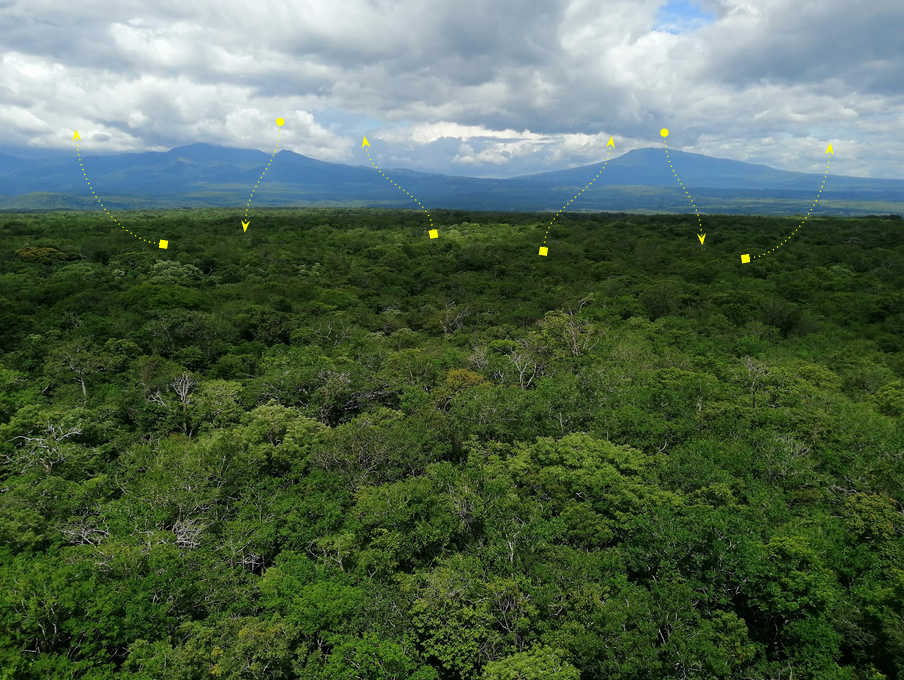

Figure 1: Santa Rosa National Park ecosystem in rainy season. Arrows represent a simplified mechanism of land-atmosphere carbon exchange

There are several methods to calculate GPP that can be grouped into two broad categories: in-situ measurements based and satellite data-driven (Guan et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2019). The Eddy Covariance technique (EC) has been the in-situ measurement method that has allowed scientists to measure directly the carbon, water, and energy fluxes between vegetation canopies and the atmosphere since before the 1990s (Baldochi et al., 2001; Ryu et al., 2019). This method to measure terrestrial fluxes is the principal approach for quantifying the exchange of CO2 between the land and atmosphere (Badgley et al., 2019; Tramontana et al., 2017).

The second category of methods to estimate GPP is the satellite data-driven models. Unlike the EC methods, these are not spatially constrained but can have more uncertainties (Ryu et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2011). Satellite data-driven models can be classified into vegetation index models (VI), light use efficiency models (LUE), and process-based models (Xie et al., 2019). VI data is derived from optical sensors that are combined with climate variables to calculate GPP (Wu et al., 2011 ). LUE models are based on the concept of radiation conversion efficiency (Monteith 1972). Process-based models explain and predict carbon fluxes taking into consideration ecological processes (Liu et al., 1997).

Rational

Vegetation indices are a summary of satellite obtained spectral data (Myneni et al., 1995) that are used to derive ecosystem biophysical variables through statistical, physical, or hybrid methods. The statistical methods relate spectral data with specific variables of interest usually with some form of regression and physical methods that associate interactions between vegetation and incoming radiation (Fernández-Martínez et al., 2019)

Show code

knitr::include_graphics("img/experimental_2.png")

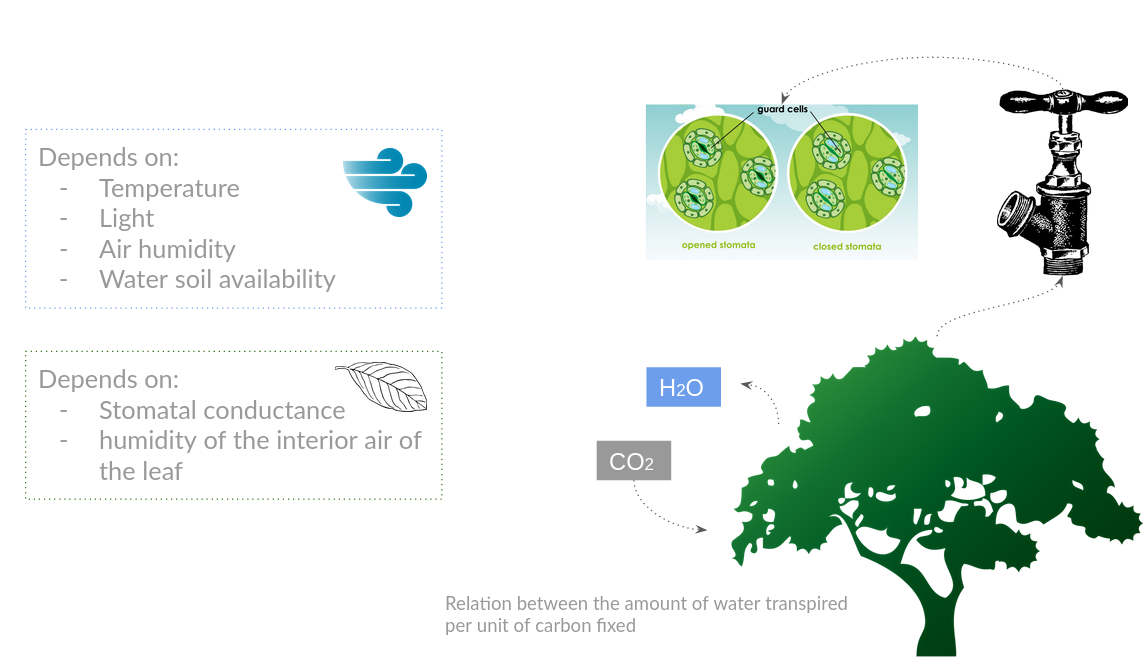

Figure 2: Factors affecting the fluxes

Given that indices are used as a proxy for photosynthetic capacity and these techniques are indirect methods to quantify GPP, an increase in uncertainties should be expected compared with in-situ methods to quantify GPP. Environmental stress factors can drive photosynthetic changes that often occur without having a major impact on canopy structure or chlorophyll content for example (Pierrat et al., 2022)

If changes on photosynthesis occur and these indices are not able to capture these changes, a mislead on the estimation of GPP and lose tracking of seasonal trends can occur.

Show code

knitr::include_graphics("img/experimental.png")

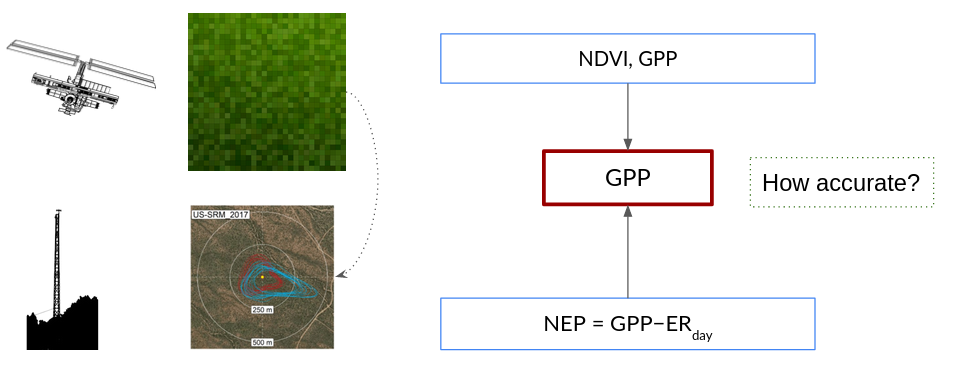

Figure 3: Comparison of GPP estimation techniques

Objectives and expected results

Objective 1

How accurate is the GPP estimation obtained from MODIS compared with the GPP estimation done with in-situ sensors?

To answer this objective we obtained the monthly estimates of GPP from MODIS Terra product and estimates made from data collected from the Eddy Covariance and sensors in-situ. A comparison of the GPP trends was done from 2013 to 2016

Objective 2

What are the main drivers of GPP in a tropical dry forest?

To answer this objective we obtained meteorological data from sensors located in-situ to understand which of these have a bigger impact on the GPP trend.

Expected results

If GPP obtained from MODIS differ with GPP calculated with Eddy Covariance method we may attribute a portion of those differences to the lack of sensitivity to photosynthetic changes that occur without a major impact on canopy structure during the initial stage of an environmental stress. Trends for GPP over a year can be evaluated and expected to be driven by high values of Vapor pressure deficit (VPD) and soil water content (SWC)

References

Anav, A., Friedlingstein, P., Beer, C., Ciais, P., Harper, A., Jones, C., … & Zhao, M. (2015). Spatiotemporal patterns of terrestrial gross primary production: A review. Reviews of Geophysics, 53(3), 785-818.

Badgley, G., Anderegg, L. D., Berry, J. A., & Field, C. B. (2019). Terrestrial gross primary production: Using NIRv to scale from site to globe. Global change biology, 25(11), 3731-3740.

Baldocchi, DD. How eddy covariance flux measurements have contributed to our understanding of Global Change Biology. Glob Change Biol. 2020; 26: 242– 260. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14807

Brown, L. A., Camacho, F., García-Santos, V., Origo, N., Fuster, B., Morris, H., … & Dash, J. (2021). Fiducial Reference Measurements for Vegetation Bio-Geophysical Variables: An End-to-End Uncertainty Evaluation Framework. Remote Sensing, 13(16), 3194.

Fernández-Martínez, M., Yu, R., Gamon, J., Hmimina, G., Filella, I., Balzarolo, M., … & Peñuelas, J. (2019). Monitoring spatial and temporal variabilities of gross primary production using MAIAC MODIS data. Remote Sensing, 11(7), 874.

Gorelick, N., Hancher, M., Dixon, M., Ilyushchenko, S., Thau, D., & Moore, R. (2017). Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote sensing of Environment, 202, 18-27.

Guan, X., Chen, J. M., Shen, H., Xie, X., & Tan, J. (2022). Comparison of big-leaf and two-leaf light use efficiency models for GPP simulation after considering a radiation scalar. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, 313, 108761.

Köhler, P., Frankenberg, C., Magney, T. S., Guanter, L., Joiner, J., & Landgraf, J. (2018). Global retrievals of solar‐induced chlorophyll fluorescence with TROPOMI: First results and intersensor comparison to OCO‐2. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(19), 10-456.

Monteith, J. L. (1972). Solar radiation and productivity in tropical ecosystems. Journal of applied ecology, 9(3), 747-766.

Myneni, R. B., Hall, F. G., Sellers, P. J., & Marshak, A. L. (1995). The interpretation of spectral vegetation indexes. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 33(2), 481-486.

Pierrat, Z., Magney, T., Parazoo, N. C., Grossmann, K., Bowling, D. R., Seibt, U., … & Stutz, J. (2022). Diurnal and seasonal dynamics of solar‐induced chlorophyll fluorescence, vegetation indices, and gross primary productivity in the boreal forest. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, e2021JG006588.

Tramontana, G., Jung, M., Schwalm, C. R., Ichii, K., Camps-Valls, G., Ráduly, B., … & Papale, D. (2017, April). Predicting carbon dioxide and energy fluxes with empirical approaches in FLUXNET. In EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts (p. 15814).

Ryu, Y., Berry, J. A., & Baldocchi, D. D. (2019). What is global photosynthesis? History, uncertainties and opportunities. Remote sensing of environment, 223, 95-114.

Wang, W., Dungan, J., Hashimoto, H., Michaelis, A. R., Milesi, C., Ichii, K., & Nemani, R. R. (2011). Diagnosing and assessing uncertainties of terrestrial ecosystem models in a multimodel ensemble experiment: 1. Primary production. Global Change Biology, 17(3), 1350-1366.

Wu, C., Chen, J. M., & Huang, N. (2011). Predicting gross primary production from the enhanced vegetation index and photosynthetically active radiation: Evaluation and calibration. Remote Sensing of Environment, 115(12), 3424-3435.

Xie, X., Li, A., Jin, H., Tan, J., Wang, C., Lei, G., … & Nan, X. (2019). Assessment of five satellite-derived LAI datasets for GPP estimations through ecosystem models. Science of the Total Environment, 690, 1120-1130.